The third Monday in February is now “President’s Day,” a vague holiday bereft of much meaning.

It wasn’t always the case.

From 1843 to 1968, February 22, no matter what day of the week it fell on, commemorated George Washington’s birthday. Years later, February 12, Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, was added to the calendar. In 1968, the U.S. Chamber of Congress lobbied Capitol Hill to turn Washington’s birthday into another three-day weekend. Families would seize the opportunity to take a vacation or to visit the grandparents. There was opposition.

“Holidays and commemorative events were not created for the purpose of trade or commerce…You have helped to destroy history for future generations,” roared Rep. Joe Waggoner (D—LA).

“If we do this, 10 years from now our schoolchildren will not know what February 22 means. They will not know or care when George Washington was born. They will know that in the middle of February they will have a three-day weekend for some reason. This will come,” predicted Rep. Dan Kuykendall (R—TN).

The moneyed interests won out. Three years later, with one sweep of the pen, President Richard Nixon did away with both holidays, creating today’s President’s Day.

In Washington’s day, New York was not a world capital. During the Revolutionary War, it was home to great drama, much of which turned out badly for Washington’s Continental Army. The rebels lost battles to the British in Brooklyn and White Plains. On Christmas evening, Dec. 25, 1776, Washington staged his surprise crossing of the Delaware River, winning battles in Trenton and Princeton and turning the tide in his favor. Prior to the revolution, during the French and Indian War, Washington had served in the British Army. He retained characteristics of an English gentlemen.

At Princeton, the Continental Army found its legs. “Parade with us, my brave fellows,” he shouted at Princeton. “There is but a handful of the enemy, and we will have them directly.” In his youth, Washington was known as the finest horseman in all of Virginia. Physically, he was up to the task of grueling battle in sub-zero temperature conditions. “It’s a fine fox chase, my boys,” he exclaimed while his troops had the British on the run.

New York City was still under British control. The rebels held the outskirts. The Continental Army rebounded with another upstate at Saratoga Springs. After victories at both Kings Mountain and the Cowpens, the action moved south. As important, the French intervened on the side of the rebels. When a French fleet traveled from the West Indies to the Chesapeake Bay, General Cornwallis moved British troops from North Carolina into Virginia.

Washington seized the opportunity to turn south and confront the British at Yorktown. There the war was won. The rebels lacked the manpower to retake New York. It didn’t matter. Cornwallis now offered his sword to the victorious George Washington.

After the war, there was the sticky business of trying to bring the 13 colonies together in one nation. For decades, politicians have badly misinterpreted e pluribus unum to be “out of many people, one,” all as an excuse for diversity. The old America was hardly diverse, as up to 80 percent of its citizens were Anglo-Saxon-Celtic Protestants, with Episcopalians such as Washington setting the pace. What the Latin phrase meant was that out of 13 colonies, one nation. Progressing from the Articles of Confederation to ratification of the U.S. Constitution was a heavy pull. The colonies, now states, were extremely jealous of their rights. Delegates from all the states were wary of being brought into a single nation under a potentially centralized—and despotic—regime. Getting states such as North Carolina and Rhode Island to ratify proved to be a major headache for Washington.

Cornwallis’s troops might have been an easier nut to crack. As president of the Continental Congress, Washington used his political skills to make the congress a success and the new nation a reality.

Those skills, along with his battlefield heroics, made Washington the natural choice to serve as the nation’s first president. Washington was a soldier and surveyor. He had to tend to his plantation at Mount Vernon. Washington was a social climber. He married the widowed Martha Fairfax, heir to Virginia’s most famous family. That included Martha’s four children from her previous marriage, not to mention the hundreds of servants and slaves who were also Washington’s responsibility. The man relented. The presidency represented Washington’s triumphant return to New York. He took a victory tour of then-bucolic Long Island, spending a night at the Onderdonk house in Roslyn, while thanking the family for their espionage service during the war.

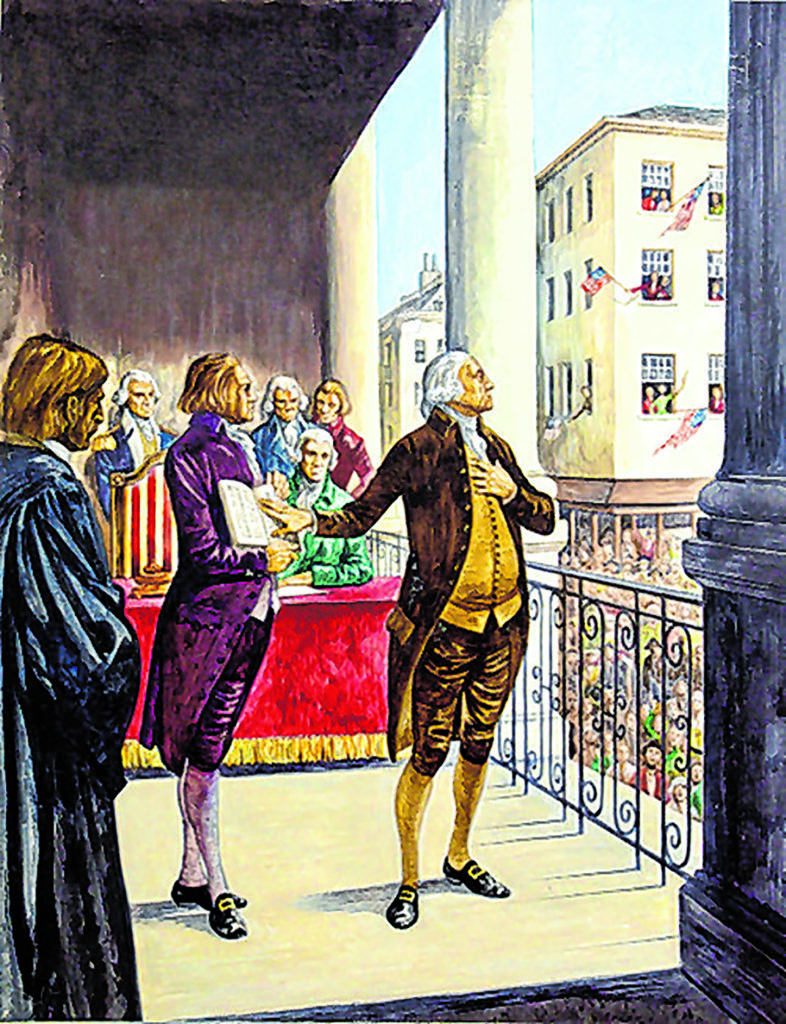

Washington was inaugurated in downtown Manhattan where most of the city’s business activity took place at the time. After taking the oath of office, an emotional Washington blurted out the now-familiar plea, “So help me God!” It was ad-libbed, not part of the speech itself.

Compared to the war and the ratification debate, Washington’s two-term presidency was remarkably uneventful. He led an army into Pennsylvania to crush that commonwealth’s Whiskey Rebellion. It had tense moments. In the end, however, there was only one casualty. In New York, Washington presided over cabinet meetings in a government that had all of four offices: State, War (now Defense), Judiciary and Treasury. Washington’s presidency featured the famous debate between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton on the nation’s financial future: Hamilton’s vision included the protective tariff as a way to raise revenue and build American industry. Jefferson was a free-trader who championed a nation of small land-owning farmers. Washington sympathized with Hamilton, while keeping his cards close to the vest. Hamilton shared Jefferson’s mistrust of a centralized regime, while the latter eventually came around to an economic policy of trade protection.

Washington’s second term made the man yearn for Mount Vernon. Newspapers ridiculed the president as a king and would-be tyrant. By 1789, Washington was glad to return to his plantation which again had fallen into disrepair. Washington’s decision to leave office after two terms made him a global phenomenon. Throughout history, men have sought—and gained—power. Once they gain power, they never relinquish it until death. Washington voluntarily left office. This was something new under the sun.

New York remains a mixed bag for Washington’s legacy. There are numerous monuments and statues to the man, including one where he took the oath of office. America is now in the grip of the greatest culture war in its history. And that includes George Washington. Brooklyn contains an equestrian monument to Washington. Also in Brooklyn, then-Borough President Marty Markowitz, under pressure from nameless black politicians, removed the portrait of Washington in that borough’s council chambers. The portrait has never gone back up again.