The literary great’s 120th birthday is next month

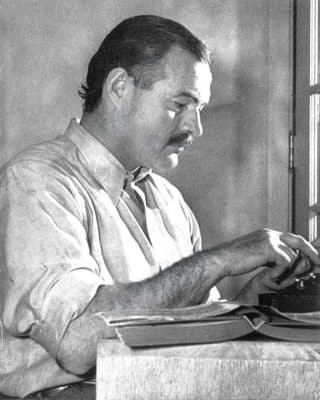

Ernest Hemingway was the emperor of the American prose narrative. With his short, declarative sentences and a view of life both heroic and tragic, Hemingway has inspired more writers and gained more imitators than any other American novelist. He wasn’t alone in fashioning a revolution in prose and poetry. By the late 19th century, the English language was getting bloated. The Romantic era had run its course. T.S. Eliot turned to the French symbolists for inspiration in both verse and new methods of expression.

Hemingway, for his part, was influenced by the great Russians, Tolstoy and Turgenev. Eliot was well-educated and multi-lingual. Hemingway could never stand four years on a college campus (it would drive him crazy), but he was no less scholarly. For both, reading bouts led to writing bouts.

Hemingway found his voice while living in Paris with his young bride. A decorated World War I veteran, Hemingway was bored with the frivolity of American life and so he arranged for newspaper work in France. In Paris, Hemingway ran with a fast crowd of expats who spent much time talking about art and life, but often little time at the writing table. The place for the in crowd was the Montparnasse, a café on the West Bank, full of gossip and intrigue. It was great fun, but Hemingway carried a great burden. The young man was full of stories. He had to take the next step and pour them out on paper.

Which he did. Hemingway retired to a quieter café down the block and got down to work on The Sun Also Rises. As important, he had started publishing short stories in those little magazines, periodicals with small circulations, but farm systems, so to speak, for budding writers. Top editors at top firms all read such publications as The Dial, Poetry and The Little Review, constantly on the lookout for up and coming talent.

Hemingway caught a break in the person and character of F. Scott Fitzgerald. The latter’s moment came in 1920 when his manuscript, This Side of Paradise, was under discussion among editors at Scribner’s. The older editors were against publication. Maxwell Perkins, however, laid down a marker: If Scribner’s wanted to take its fiction list into the new century, it would have to start with novels like the one the young Fitzgerald had submitted. The talented young man from St. Paul would get published and in time, establish himself as the voice of the Jazz Age.

Fitzgerald was also exceedingly kind with fellow authors. He envisioned Scribner’s as the publishing capital of American letters. He boosted Hemingway to Perkins. Hemingway’s short stories eased the way to publication of The Sun Also Rises. Fitzgerald also edited the manuscript, excising the initial chapter and starting the manuscript with the famous lines, “Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton.” Think of Ezra Pound’s editing of Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” It’s so similar as to be downright eerie.

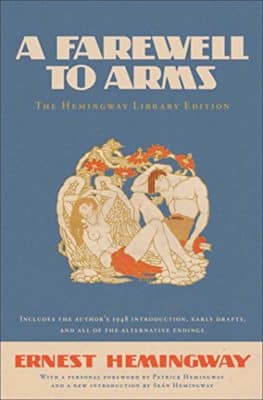

With The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway captured the anxieties of the 1920s. His image was that of a swashbuckler, a hunter, a fisherman, a daring soldier. That was true, but Hemingway was a disciplined man. Five hours at the writing table took precedent over hunting and fishing expeditions. His upbringing was thoroughly middle class, the second child of six of an Oak Park, IL physician and a domineering mother. Hemingway’s father was a suicide, always bad news for the surviving sons.

For many an American boy, World War I was a chance for adventure, a way to escape the home front and find war glory in Europe. Hemingway’s wartime heroics were no myth. An ambulance driver, he became a hero to Italians for saving lives during combat. Back home in Illinois, he pined for Europe and its unfolding tragedy.

Hemingway was workman-like. If he was going to live as an expatriate, he would have to come through. Short stories, novels, non-fiction tumbled from his pen: To Have And Have Not, Death In The Afternoon, Green Hills of Africa and the stories: “The Killers,” “A Way You’ll Never Be,” “The Gambler, The Nun and The Radio,” “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.” Hemingway was very much a man of 1914, joining Eliot, Pound, James Joyce and Wyndham Lewis. The tragic grandeur of the postwar world meant a search for nobility in a shattered world.

It worked. When Hemingway started publishing, he declared that his work would be read by both high school dropouts and PhDs. It was. In 1938, Scribner’s brought out The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, a publishing event and a volume that once stood on the bookshelf of virtually every home in America. In 1940, Hemingway published his novel of the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls. Perkins loved the novel (as did the public), but the legendary editor told friends that this was it for Hemingway. The man, Perkins was positive, had just published his last great novel.

Was it true? In 1951, Hemingway published a shorter novel, Across the River and Into the Trees. The critics were laying in wait, eager to take down the Champ of American Letters. The novel received poor reviews. Hemingway was a fighter (he managed a pro named Hank Ketchum and worked out in the ring on a regular basis). He rebounded two years later with The Old Man and The Sea, a novella set in the Caribbean. Hemingway’s heroes often died at the end of their adventures. However, Mary Walsh, Hemingway’s fourth wife, begged him not to kill off Santiago, the novella’s hero. Mary prevailed. The Old Man and The Sea was a sensation. Excerpted in its entirety in Life magazine, the issue sold five million copies off the newsstands. Publication brought a Pulitzer Prize and the 1953 Nobel Prize. Hemingway, the old prizefighter, was off the canvas and back on top.

Throughout the 1950s, Hemingway continued writing. But he did not publish. Was he afraid that works in progress—Islands in The Stream, The Garden of Eden, The Dangerous Summer—couldn’t live up to past efforts? Did he fear losing his crown? Hemingway loved Cuba. He was more at home there than in Paris or his home country. When Fidel Castro took power in 1960, Hemingway was advised by State Department officials to get out and in a hurry. Hemingway re-located in Idaho. It wasn’t enough. Hemingway’s death was first reported as a gun-cleaning accident. The truth came out a few days later.

Suicide wasn’t the end of Hemingway the published writer. After the shock wore off, there was poor Mary Hemingway, trudging up Fifth Avenue on the way to Scribner’s, manuscripts in a shopping bag. The mortal man was gone, but in the years ahead, his readers would stay plenty busy.