“You’re entering God’s country.” So said former New York Mets great John Franco, when talking about driving across the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge his adopted hometown of Staten Island. Or was he talking about taking the bridge from that island to his real hometown, Brooklyn, USA? It doesn’t matter. Both boroughs represent God’s country.

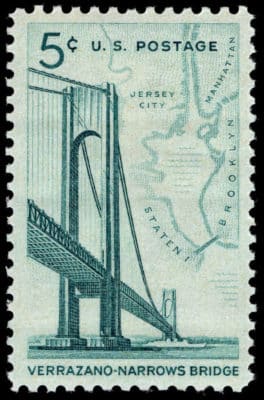

And what connects them both is that same bridge. The construction of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge was completed in 1964. It was an historic event, connecting the formerly sleepy Staten Island to the New York metropolis.

The bridge is named after Giovanni da Verrazzano, a 16th-century Italian explorer who was the first European to scout the Eastern seaboard, sailing there from France in 1524. For years, Henry Hudson, of Hudson River fame, was considered the first explorer to achieve that goal. But as Verrazzano’s fame grew, the latter, who died under mysterious conditions in 1528, was credited with this monumental discovery.

Construction on the bridge began in 1958, the culmination of a project that was first floated during the Roaring ’20s. In 1926, with the city flush with money, engineers began proposing a bridge to link Staten Island with the rest of the city. For decades, the idea followed a rocky road. The 1929 stock market crash hurled the nation into a depression, throwing cold water on many construction plans. In 1934, the War Department opposed the new bridge, with generals maintaining that increased traffic would hamper traveling conditions in time of war.

By 1936, the idea of a tunnel rather than a bridge was being considered. The city’s popular mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, supported such a plan. However, residents of Bay Ridge opposed a tunnel. LaGuardia, ever the in-touch politician, dropped his support and it was back to the drawing board for a bridge.

After World War II, the country was booming again. The bridge idea was revived. In 1955, Gov. W. Averell Harriman signed a spending bill, providing funds not just for a “Narrows Bridge,” but also the Throgs Neck Bridge connecting Queens and the Bronx and a second level to the George Washington Bridge. As important was the contribution of Robert Moses, the legendary chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA) who re-configured postwar New York. In 1947, Moses sought and received permission from the War Department for bridge construction. This was Moses’s baby, now. The man played hardball, warning Mayor Robert Wagner in a 1958 letter that if the latter abandoned the Seventh Avenue, Bay Ridge approach to the bridge, then the entire project would be dropped. In 1959, groundbreaking took place. In November 1964, the bridge was open for business.

Right away, the bridge was popular. In the first two months, traffic totaled 1.86 million vehicles, a number higher than expected. That meant added revenue. Still, there were complications. Starting the bridge in the Seventh Avenue section neighborhood resulted in the dislocation of 7,500 unsuspecting residents, continuing a dismal postwar trend of uprooting working-class and middle-class residents for the sake of bridge and highway construction, the most dramatic being the Cross Bronx Expressway.

Also controversial was the name. Verrazzano is spelled with two ‘z’s. The bridge only came with one ‘z.’ Little Staten Island was set for a growth in population. Not everyone liked it. Locals referred to it as the “guinea gangplank,” noticing the large number of Italian-Americans who left South Brooklyn for the more rustic reaches of Staten Island. Media outlets omitted references to Verrazzano, opting to identify the structure as the Narrows Bridge, or the Brooklyn–Staten Island Bridge. Lobbying by the Italian Historical Society of America rectified the latter omission.

The bridge remains a marvel of the modern world. With its completion, it surpassed San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge as the world’s longest suspension structure, a title it held until 1981, when the Humber Bridge in England was built. In all, the bridge contains up to 1 million bolts and 3 million rivets. Its size is staggering. The towers amount to 1,129,000 long tons of steel, a number significantly greater than the 365,000 tons used to construct the Empire State Building. An average of 202,523 vehicles cross it each day in both directions. Starting in 1976, the bridge was used as the starting point for the annual New York City marathon.

The bridge, too, has figured in popular culture. It was prominent in 1977’s Saturday Night Fever, the film that launched John Travolta’s movie career. Travolta’s character, Tony Manero and his Bay Ridge pals, enjoyed clowning around on the bridge, frightening and fooling the loyal girlfriend, Annette. There are also poignant moments. Manero liked to stare at the bridge and draw an imaginary line through it, symbolizing his own desire to make the move to Staten Island. Manero was too much a mama’s boy to light out on his own. Another girlfriend, Stephanie, made her own move to Manhattan. She inspires Manero to finally make it out of Bay Ridge and into the big city.