Downtown Manhattan was the first writer’s haven

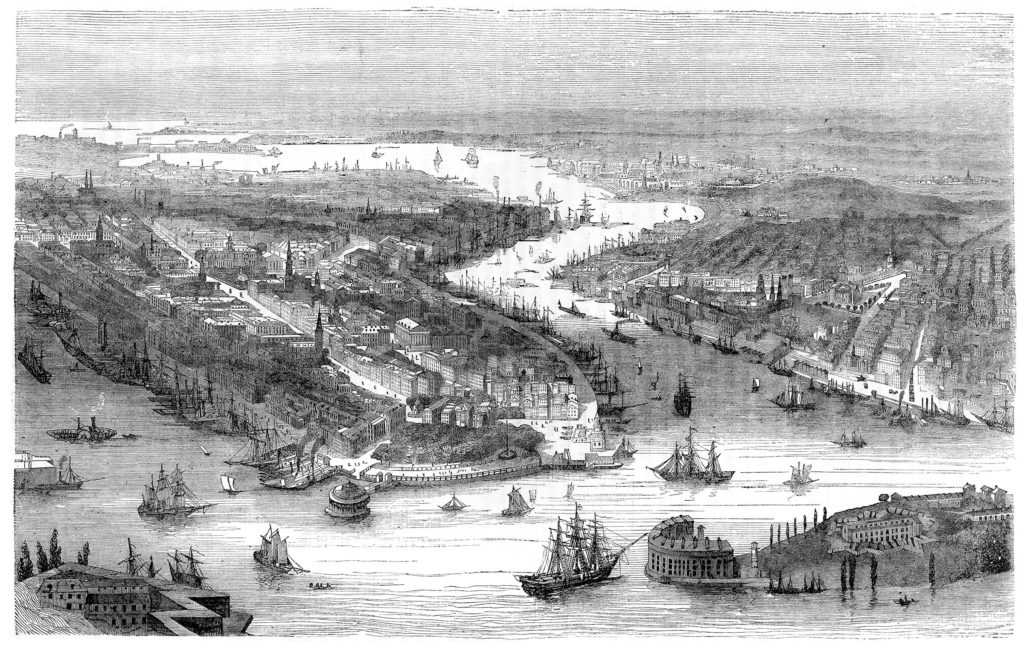

When New York City was settled during the 17th century, downtown Manhattan was the center of activity. The rest of the borough, not to mention everywhere else in the New York area, was farmland. Downtown was the center of commercial and political activity. New York’s first newspaper, the New York Gazette, was founded in 1725. In those days, publications were not considered journalism, instead their goal was to advance a certain political party, while running down any competitors.

Such advocacy reached a peak in 1787 and 1788, when three of the Founders—John Jay, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton—co-authored The Federalist Papers, an apology for the ratification of the United States Constitution that appeared in serial form in several publications and then in book form. The volume has remained an American classic ever since, studied by generations of budding historians.

Pamphleteering was also popular in the old America. New York as a haven for writers began with Thomas Paine and the publication of Common Sense (1776). Paine was a British national who enthusiastically supported the American Revolution. He also had a house in today’s Greenwich Village. The address was symbolic as the Village, starting in the late 19th century, would stand as a hub of creativity, not just in literature but in music and art as well, attracting ambitious youngsters from all over the country to New York.

With ratification, history would be the next step in developing a literary New York. Another famous name that lives on is Washington Irving. A prolific author, Irving penned a satirical book, A History of New York by Diedrich Knickerbocker (1809) which was well-received overseas. Both Charles Dickens and Samuel Taylor Coleridge were fans of the book, enhancing both the author and the volume. At home, the history reigned for decades as the best-selling book in the young nation. Irving later published a popular biography of George Washington and the much-beloved classic, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820).

Another novelist who enhanced New York’s literary reputation was James Fenimore Cooper. Irving lived on Williams Street. Cooper had a house on Greenwich Street. Cooper is legendary as the author of The Leatherstocking Tales, a series of five novels published between 1827 and 1841 and set in upstate New York. His city novel was also satirical, with Home as Found (1832), criticizing the pretentious ways of the city’s high society. That theme has never grown old, used in later decades with great effectiveness by such talents as Truman Capote and Tom Wolfe.

Cooper was also a generous man, befriending many young writers. One of them was William Cullen Bryant, who also wrote poetry. As editor of the New York Evening Post, Bryant combined newspapers, advocacy and poetry, setting a pattern followed by many writers who came after him, including Edgar Allan Poe and Walt Whitman. Bryant was more polemical. A staunch abolitionist, Bryant introduced Abraham Lincoln when the latter gave his famous Cooper Union speech in 1860.

These men played a major role in establishing the city as a literary counterpoint to Boston, which by the 19th century, was well-established as the literary capital of the United States. When Bryant and Whitman first published their verse, gaining the approval of such mandarins as Ralph Waldo Emerson was key in securing their fame.

In time, the literary action would move slightly uptown to Greenwich Village. But these men made their mark. The U.S. Constitution is that era’s most enduring monument.

Today’s New York includes an Alexander Hamilton High School and a James Madison High School, both in Brooklyn, plus a John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan. A handsome statue of Washington Irving sits outside a high school named for the man in the Gramercy Park area. Manhattan also boasts of Bryant Park in midtown, plus the renovation of Cedarmere, Bryant’s estate in Roslyn Harbor.

Downtown means Wall Street, and with the stock market boom of the 1980s and beyond, that once-staid club became a model for fiction, most spectacularly in Tom Wolfe’s 1987 best-seller The Bonfire of the Vanities, where stockbrokers now fancied themselves as the new “masters of the universe.” Earlier, Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City (1984) predicted the transforming effects of the coming digital age and signaled the return of the downtown area as a locale for fiction. McInerney’s later novels, including Brightness Falls (1992) and Bright, Precious Days (2016), also used the ups and downs of Wall Street as the background for fictional drama.

The wheeling and dealings on Wall Street are likely to remain a gold mine for future novelists. Money, after all, is the New York religion.