Le Clercq’s creative legacy beyond dance

Ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq glides across the stage with a sensual elegance in Afternoon of a Faun, a ballet choreographed by Jerome Robbins. Le Clercq, principal ballerina of the New York City Ballet during the 1940s and 1950s, captivated audiences with her charismatic stage presence, technique and long-limbed physique. The wife and muse of choreographer George Balanchine, Le Clercq was at the height of her career in 1956 when she was stricken with polio while on tour in Europe. Left paralyzed from the waist down, she would never dance or walk again.

While her story is tragic, Le Clercq’s creative and artistic legacy transcends her career as a dancer, asserts food scholar and writer Meryl Rosofsky, an MD from Harvard who is an adjunct professor in the Department of Nutrition and Food Studies at New York University.

“Tanaquil Le Clercq’s ballet legacy is first and foremost. She originated roles in a number of iconic ballets that are forever linked to her. The image of her in these roles has rarely ever been equaled,” said Rosofsky. “Yet she lived many years after her life as a dancer came to this tragic, abrupt end.”

Channeling her creative impulses into new outlets, Le Clercq wrote two books and taught dance at Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Rosofsky recalls how she discovered The Ballet Cook Book.

Rosofsky recalls how she discovered The Ballet Cook Book.

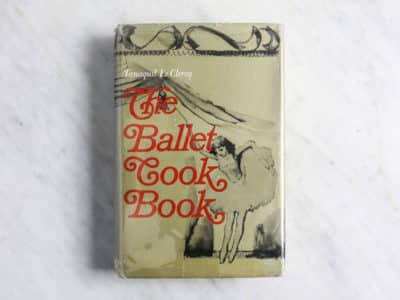

“Hearing that Balanchine was a great cook was a revelation for me,” she said. “I started to Google him and came upon The Ballet Cook Book. I got a copy. It was love at first sight. The book is filled with wit, humor, gems of ballet history, and is so personal and at the same time so universal.”

A 2016 fall fellow at the Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University, Rosofsky’s project, “Breaking Bread with Balanchine: On Food, Cooking, and the Creative Impulse in Choreography,” explored Balanchine’s connection to food and the culinary significance of Le Clercq’s Ballet Cookbook. Published in 1966, the cookbook, now out of print and treasured by collectors, is an international collection of the stories and recipes of more than 90 leading dancers and choreographers of the period, including Rudolph Nureyev, Margot Fonteyn, Edward Villella, George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins.

“We do not think of Tanaquil just as a great dancer struck down by polio,” said Rosofsky. “She was a remarkable, brave woman, a gatherer of stories and cook in her own right.”

Rosofsky recently curated a program at the Guggenheim Museum in New York to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the publication of The Ballet Cookbook. Part of the museum’s Works & Process performance series, the event included a panel discussion with dance legends Jacques d’Amboise and Allegra Kent—both contributors to Le Clercq’s cookbook and present at the book signing 50 years ago—and New York City Ballet principal dancers Jared Angle and Adrian Danchig-Waring. A slideshow of photos and film footage of Le Clercq and Balanchine was interspersed with excerpts of ballets originated by Le Clercq that were performed by current New York City Ballet dancers. Also, the museum’s Wright restaurant served a selection of dishes from the cookbook, including Le Clercq’s Chicken Vermouth, George Balanchine’s Slow Beet Borschok, Melisa Hayden’s Potato Latkes and Allegra Kent’s Walnut Apple Cake.

For the project, Rosofsky interviewed Balanchine’s contemporaries and perused the archives at Columbia University and the New York Library for The Performing Arts.

“Tanaquil was born in Paris. Her marriage got her into food. They entertained. Food was a large part of their lives as a couple,” she said. Before leaving on a three-month dance tour of the Soviet Union in 1962, Balanchine encouraged Le Clercq to work on the cookbook project, Rosofsky said. Her first book, Mourka: The Autobiography of a Cat, had been published the year before.

Rosofsky is not surprised by the idea of a ballet cookbook.

“Dancers might have to think about what they eat—they’re elite athletes,” she said, adding that there is a connection between dance, choreography, and food and cooking. “Both rely on technique, timing, technology. Both have rules, structure, but also improvisation, experimentation. Both are civilizing and elevating. They are part of the ritual and impulse that makes it wonderful to be human and alive. A gift you can give to others and yourself.”

As she dug deeper, Rosofsky said a rich, amazing story began to emerge.

“Tanaquil, and the story of her cookbook started to take shape. One of the things I discovered was the book launch at Bloomingdales, so exciting, I found pictures taken by ballet photographer Martha Swope, and it turns out my husband’s mother, Melissa Hayden, was there. Here are images speaking to me from the past,” she said, adding that her husband had attended as well, as a child. “This story that had so captivated me took on a personal meaning as well.”

Teacher, writer—Le Clercq was all of these things, said Rosofsky.

“Her two books are remarkable achievements,” she said. “The Ballet Cook Book is beautifully written, full of these amazing anecdotes and stories and with such a great voice, you could hear her leaping off the page. She now has this culinary legacy.”

Rosofsky hopes to spark a response to Le Clercq’s inspiring life story by republishing the cookbook with essays to frame the story for a modern audience. She also would like to compile a New Ballet Cookbook of the family recipes and holiday traditions of today’s dancers and choreographers, a “culinary time capsule for people 50 years from now.”