The entrance lobby of the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Battery Park is a bright, boisterous place—an open rotunda with a high ceiling that lets in the light of the day. Tour groups and school children make their way around the building.

It’s noisy, it’s a place of life.

Except for one corridor off to the right, a black hallway lurking at the edge of view in stark contrast to the surrounding environment. That’s the entrance to the museum’s newest exhibit, “Auschwitz: Not Long Ago, Not Far Away,” the largest-ever collection of artifacts documenting the Nazi death camp and the town its presence changed forever.

Through that tunnel is a different world, a world dedicated to peoples and cultures decimated by the brutality of the Holocaust. The exhibit focuses on that loss right from the start, immediately presenting viewers with archival footage from families killed in the camp. Children laughing, old men leaving temple—everyday scenes of lives long since erased.

At the end of that hallway, a quote from Holocaust survivor Primo Levi presents what one tour guide called the message of the entire exhibit.

“It happened, therefore it can happen again,” Levi’s quote read. “This is the core of what we have to say. It can happen, and it can happen anywhere.”

Things grow quiet on the other side of that tunnel. What few words get uttered between guests are spoken in hushed whispers, as if the enormity of this place demands silent reverence. Every now and then, a sob breaks that silence.

The exhibit chronicles the developments that led to the Holocaust with meticulous detail. The history of Europe’s Jews, the pain of Germany’s loss in the First World War and the way that pain was harnessed by a long-bubbling backdrop of antisemitism into the catalyst for Nazi Germany, every part of the story is told through photos, artifacts and walls of text.

The camp itself, the exhibit reveals, was placed in that old town the Polish called Oswieicm because of its importance as a railway juncture. For 100 years, it was a crucial intersection of routes from all over Eastern Europe, bringing travelers from across the continent and functioning as a safe haven for thousands of Jews around the turn of the 20th century.

Those same railways that brought life into Oswiecim would fuel Auschwitz throughout its entire operation.

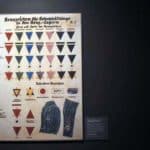

Most of the exhibit focuses on the trauma Europe’s Jewish community was subjected to under Nazi rule, but considerable space is dedicated to telling lesser-known stories of the other minorities and social outcasts subjected to the death camps. The Romani were atomized by the Holocaust, too, as about 1.5 million of them perished during its run. They just called it the “Porajmos,” which translates to “The Devouring.” Auschwitz slaughtered gay people, Poles and socialists, too, all of who receive their dedicated space to chronicle their experience at the camp.

Some of the most powerful parts of the exhibit are massive relics from the camp. There’s a pair of wheels from a railroad car that ferried prisoners into Auschwitz, each the size of a person. Across the room stand pillars and barbed wire from the fences that enclosed the camp. Strands of the frayed metal are missing, but the pieces that remain survived from when they were used to trap human beings.

Some of the exhibit’s most powerful artifacts are small things, trinkets left behind by departed victims of Nazi terror. Photos showing piles of discarded glasses, shoes and suitcases are infamous the world over, but it’s a different thing entirely to see worn leather soles that belonged to a little girl from Poland, suspended in a glass box and complete with a story of the child who used to run through her hometown wearing them.

Perhaps the most poignant piece is a group of three small beans laid atop a sheet of glass. Those beans were food given to Anne Frank and her family as they hid from Nazi soldiers in a secret room in Amsterdam. She wrote about them in her diary.

Years later, after escaping Auschwitz, her father Otto returned to the house that now bears her name and found these same beans alone on the floor—tangible remnants of his teenage daughter. They wait now at the museum.

The sheer scope and depth of documentation at the exhibit is daunting. Until it moves on Jan. 3, 2020, it will stand in New York as an embodiment of how important it is to never forget what happened at Auschwitz.